Compound interest is the mechanism that makes money grow faster over time by earning “interest on interest.” It is simple in concept, but the real-world outcomes depend heavily on time, rate, compounding frequency, and whether you add ongoing deposits.

This guide explains:

- What compound interest is and why frequency matters

- The difference between APR and APY

- The key formulas (in reusable format)

- Worked examples, including tables

- How regular deposits accelerate growth and why the timing of deposits matters

1) What Compound Interest Is

Simple interest pays interest only on the original principal.

Compound interest pays interest on the principal and on previously earned interest.

If you start with a balance P and earn interest, your balance becomes larger. Next period, interest is calculated on that larger balance, so the growth rate accelerates over time.

The basic compounding idea

After one compounding period at periodic rate r_p:

Balance_1 = P * (1 + r_p)

After n periods:

Balance_n = P * (1 + r_p)^n

Where:

P= starting principalr_p= interest rate per compounding periodn= number of compounding periods

2) Compounding Frequency: Why It Matters

Compounding frequency is how often interest is added to your balance:

- Annual (1×/year)

- Semiannual (2×/year)

- Quarterly (4×/year)

- Monthly (12×/year)

- Daily (365×/year or 360×/year depending on convention)

- Continuous (the theoretical limit)

All else equal, more frequent compounding produces a slightly higher ending balance, because interest is credited earlier and begins earning interest sooner.

3) APR vs APY: What’s the Difference?

These terms are often used interchangeably in everyday conversation, but they represent different things.

APR (Annual Percentage Rate)

APR is typically a nominal annual rate. It does not fully reflect compounding unless explicitly stated. It is commonly used for loans and stated interest rates.

- APR answers: “What is the stated annual rate before compounding effects?”

APY (Annual Percentage Yield)

APY reflects the effective annual rate, including compounding. It shows what you actually earn in a year if interest compounds and stays in the account.

- APY answers: “What is the effective yearly growth rate after compounding?”

Converting APR to APY (for compound interest)

If APR is r and compounding happens m times per year:

APY = (1 + r/m)^m - 1

Where:

ris the nominal annual rate (APR as a decimal, e.g., 0.06 for 6%)mis compounding frequency per year

Converting APY to APR (if needed)

If you know APY and m:

APR = m * ((1 + APY)^(1/m) - 1)

4) Core Compound Interest Formula (Lump Sum)

If you deposit a lump sum P, with APR r, compounded m times per year, for t years:

FV = P * (1 + r/m)^(m*t)

Where:

FV= future valueP= principalr= APR (decimal)m= compounding periods per yeart= time in years

5) Example: Same APR, Different Compounding Frequencies

Assume:

- Principal

P = 10,000 - APR

r = 6% = 0.06 - Time

t = 10 years

Compute future value with different m.

Results table

| Compounding | m | Future Value Formula | Future Value (Approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Annual | 1 | 10,000*(1+0.06/1)^(1*10) | 17,908 |

| Quarterly | 4 | 10,000*(1+0.06/4)^(4*10) | 18,145 |

| Monthly | 12 | 10,000*(1+0.06/12)^(12*10) | 18,194 |

| Daily | 365 | 10,000*(1+0.06/365)^(365*10) | 18,221 |

Interpretation: More frequent compounding increases the ending balance, but the difference is usually modest at typical interest rates. Over longer time horizons or higher rates, the gap becomes more noticeable.

6) APY: What 6% APR Becomes as APY

Using:

APY = (1 + r/m)^m - 1

with r = 0.06:

| Compounding | m | APY (Approx.) |

|---|---|---|

| Annual | 1 | 6.000% |

| Quarterly | 4 | 6.136% |

| Monthly | 12 | 6.168% |

| Daily (365) | 365 | 6.184% |

| Continuous | ∞ | 6.184% |

The “ceiling” here is the continuous compounding limit:

APY_continuous = e^r - 1

So at 6% APR:

APY_continuous ≈ e^0.06 - 1 ≈ 6.184%

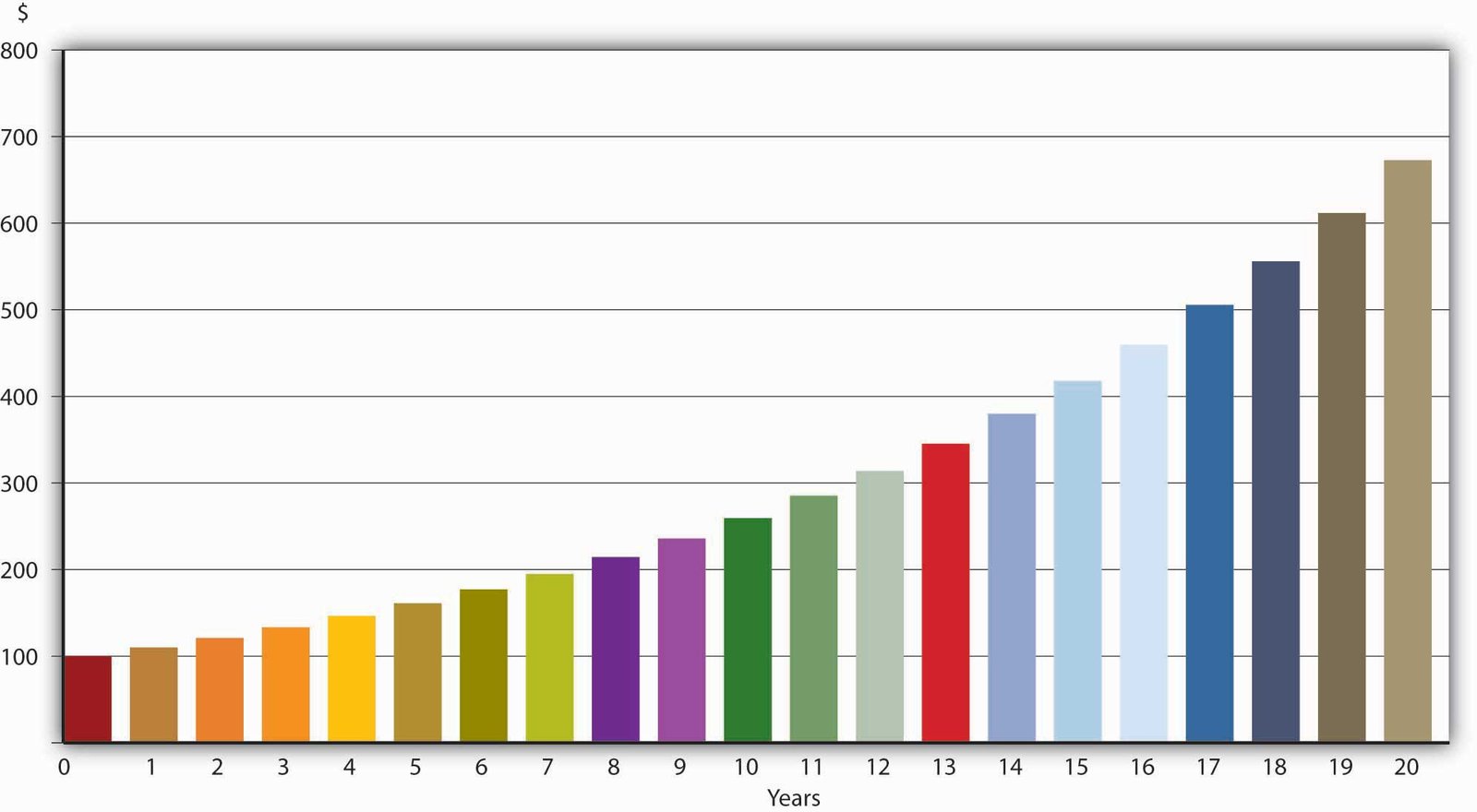

7) Deposits Accelerate Results: Lump Sum vs Regular Contributions

Compounding is powerful, but compounding plus ongoing deposits is where results often change dramatically. Even modest recurring contributions can dominate outcomes over time.

There are two common contribution patterns:

- Deposits at the end of each period (ordinary annuity)

- Deposits at the start of each period (annuity due)

Deposits made earlier have more time to compound.

8) Future Value With Regular Deposits (Ordinary Annuity)

Assume:

- Periodic deposit =

PMT - APR =

r - Compounding per year =

m - Total years =

t

Periodic rate:

i = r/m

Number of periods:

n = m*t

Future value of deposits (end of each period):

FV_deposits = PMT * [((1 + i)^n - 1) / i]

If you also have a lump sum principal P:

FV_total = P*(1 + i)^n + PMT * [((1 + i)^n - 1) / i]

9) Example: Monthly Deposits vs No Deposits

Assume:

- Initial principal

P = 10,000 - APR

r = 6% - Monthly compounding (

m = 12) - Time

t = 10 years(n = 120) - Monthly deposit

PMT = 200(end of month)

Periodic rate:

i = 0.06/12 = 0.005

Lump sum growth alone

FV_lump = 10,000*(1.005)^120 ≈ 18,194

Deposits growth

FV_deposits = 200 * [((1.005)^120 - 1) / 0.005]

Compute the growth factor:

(1.005)^120 ≈ 1.8194

So:

FV_deposits ≈ 200 * [(1.8194 - 1)/0.005]

≈ 200 * [0.8194/0.005]

≈ 200 * 163.88

≈ 32,776

Total future value

FV_total ≈ 18,194 + 32,776 = 50,970

Interpretation: The monthly deposits contribute a large portion of the final balance—more than the growth of the initial principal—because you are injecting new capital continuously.

10) Deposit Timing: End of Period vs Start of Period

If deposits happen at the start of each period, each deposit earns one extra period of interest. This is called an annuity due.

Future value of deposits (start of each period):

FV_due = FV_ordinary * (1 + i)

So with monthly rate i = 0.005, the annuity due value is about:

FV_due ≈ FV_ordinary * 1.005

This difference seems small per month, but over many years it adds up—especially with larger deposits.

11) How Frequency Changes Growth at the Same APY

Sometimes accounts advertise APY rather than APR. If APY is fixed, the compounding frequency is already “baked in,” and the effective annual growth is the same (assuming the APY is accurately stated and interest is retained).

However, in practice, frequency can still matter due to:

- When deposits are credited

- When interest is calculated (daily balance vs average balance)

- When withdrawals happen

- Whether interest starts immediately or after a holding period

To evaluate accounts accurately, you typically want to confirm:

- Is interest calculated daily?

- Is it compounded daily or monthly?

- When are deposits considered “in balance” for interest?

12) Common Real-World Details That Affect Compounding

1) Interest calculation method

Some accounts compute interest on:

- Daily ending balance

- Average daily balance

- Minimum balance in a period

Daily-balance methods tend to reward earlier deposits more directly.

2) Fees

Fees reduce your effective return. A small monthly fee can materially reduce the real outcome, particularly for small balances.

A simplified way to incorporate fees is to treat them as negative cash flows and compute an internal rate of return (IRR) or net growth.

3) Taxes (if applicable)

If interest is taxed annually, your effective compounding can be lower than the headline APY because a portion of earned interest is removed each year.

13) Practical Heuristics (That Actually Hold Up)

- Time matters more than frequency.

Monthly vs daily compounding is a small difference compared to investing for 30 years instead of 10. - Deposits matter more than you think.

Regular contributions often dominate the outcome because they increase the base that compounds. - Earlier deposits beat later deposits.

Even one period earlier helps; over many periods, it becomes meaningful. - APY is usually the cleanest comparison metric for savings products.

If two accounts have different compounding schedules, APY allows apples-to-apples comparison—assuming the APY is stated consistently.

14) Quick Reference Tables

A) APR → APY conversion examples (illustrative)

| APR | Monthly APY (Approx.) | Daily APY (Approx.) | Continuous APY (Approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3% | 3.042% | 3.045% | 3.045% |

| 6% | 6.168% | 6.184% | 6.184% |

| 10% | 10.471% | 10.515% | 10.517% |

B) “Rule of 72” (quick doubling estimate)

A fast way to estimate how long it takes to double at a given annual rate r%:

Years_to_double ≈ 72 / r

Example: at 6%:

72 / 6 = 12 years (approx.)

This is a rough heuristic, but useful for sanity checks.

FAQs

1) What is compound interest in one sentence?

Compound interest is interest calculated on both the original principal and the accumulated interest from prior periods.

2) What does compounding frequency mean?

It’s how often interest is added to your balance (monthly, daily, etc.). More frequent compounding generally yields slightly higher growth at the same APR.

3) How is APY different from APR?

APR is typically the stated nominal annual rate. APY is the effective annual rate after compounding:

APY = (1 + r/m)^m - 1

4) If an account advertises APY, does frequency still matter?

If APY is accurately stated and interest is retained, APY already reflects compounding. Frequency may still matter for cash flow timing (when deposits and withdrawals occur) and how interest is computed (daily balance vs average balance).

5) How do regular deposits change compound interest results?

They add new principal that can compound. The future value of recurring deposits is:

FV_deposits = PMT * [((1 + i)^n - 1) / i]

6) Are deposits at the beginning of the month better than at the end?

Yes. Beginning-of-period deposits compound for one extra period:

FV_due = FV_ordinary * (1 + i)

7) Why do small differences in rate matter so much over time?

Because compounding is exponential. Over long periods, even small rate differences multiply into large gaps.

8) What is continuous compounding?

It is the theoretical limit of compounding frequency:

FV = P * e^(r*t)

APY = e^r - 1

9) What’s the single biggest driver of compounding success?

Time, followed closely by consistent contributions. Frequency differences are usually smaller in comparison.

10) How can I compare two savings accounts fairly?

Compare APY (net of fees if possible), confirm how interest is calculated, and check any balance tiers or conditions that affect the stated yield.