Money decisions often feel complicated because the numbers are expressed in different “languages”: monthly payments versus annual rates, nominal growth versus real purchasing power, or “interest rate” versus “effective rate.” Finance math is simply the translation layer.

This guide focuses on the most common formulas behind:

- Savings growth (with and without regular contributions)

- Loans and amortization (how payments are calculated and split)

- Interest rates (simple, compound, effective annual rate)

- Basic investing math (returns, CAGR, risk, and inflation adjustment)

You do not need advanced mathematics. Most of what people use in everyday finance comes down to compounding, discounting, and cash-flow timing.

Key Notation Used in This Guide

To keep formulas consistent, we’ll use:

P= principal (starting amount)FV= future valuePV= present valuer= annual interest rate (as a decimal; 5% = 0.05)i= periodic interest rate (e.g., monthly rate)n= number of periods (months, years, etc.)PMT= periodic payment (loan payment or savings contribution)m= compounding periods per year (12 monthly, 4 quarterly, etc.)

1) Percentages and Rate Conversions (The Building Blocks)

Converting percent to decimal

decimal_rate = percent / 100

Example: 7% becomes 0.07.

Annual rate to periodic rate

If an annual rate is compounded m times per year:

i = r / m

Example: 12% nominal compounded monthly:

r = 0.12m = 12i = 0.12 / 12 = 0.01(1% per month)

Number of periods

n = years * m

Example: 5 years with monthly periods:

n = 5 * 12 = 60months

These two conversions (i and n) are used in almost every loan and savings calculation.

2) Simple Interest vs Compound Interest

Simple interest (rare in long-term products)

Simple interest grows only on the original principal:

FV = P * (1 + r * t)

Where t is time in years.

Example: P = 1,000, r = 0.06, t = 3

FV = 1,000 * (1 + 0.06 * 3) = 1,180

Total interest = 180.

Compound interest (the default in modern finance)

Compound interest grows on principal and accumulated interest:

FV = P * (1 + i)^n

If you’re using annual compounding, i = r and n = years.

Example: P = 1,000, r = 0.06, t = 3

FV = 1,000 * (1.06)^3 ≈ 1,191.016

Compound produces slightly more than simple interest because interest earns interest.

3) Effective Annual Rate (EAR): Comparing Like-for-Like

A common mistake is comparing rates that compound differently. A “10% compounded monthly” is not the same as “10% compounded annually.”

The effective annual rate converts compounding into a true one-year growth rate:

EAR = (1 + r/m)^m - 1

Example: 12% nominal, compounded monthly

r = 0.12m = 12

EAR = (1 + 0.12/12)^12 - 1

= (1.01)^12 - 1

≈ 0.126825

So the effective annual rate is about 12.6825%, not 12%.

Quick comparison table (same nominal rate, different compounding)

Nominal Rate (r) | Compounding (m) | Effective Annual Rate (EAR) |

|---|---|---|

| 10% | 1 (annual) | 10.0000% |

| 10% | 4 (quarterly) | 10.3813% |

| 10% | 12 (monthly) | 10.4713% |

| 10% | 365 (daily) | 10.5156% |

This matters for both savings products and debt, especially when fees are also present.

4) Present Value (PV): What Future Money Is Worth Today

If money can grow at some rate, then money received later is worth less today. That is the idea behind discounting.

Present value of a single future amount

PV = FV / (1 + i)^n

Example: You will receive FV = 5,000 in 4 years. Discount rate is 6% annually.

PV = 5,000 / (1.06)^4 ≈ 3,960.32

Meaning: at 6%, about 3,960 today grows to ~5,000 in 4 years.

PV is fundamental for comparing offers, pricing long-term projects, and evaluating investments.

5) Future Value With Regular Contributions (Savings Growth)

Most people build savings through repeated contributions. This is the future value of an annuity.

Future value of periodic contributions (ordinary annuity)

Assuming contributions happen at the end of each period:

FV = PMT * [((1 + i)^n - 1) / i]

Example: Save PMT = 200 per month, for 5 years, at 6% annual compounded monthly.

r = 0.06m = 12i = 0.06/12 = 0.005n = 60

FV = 200 * [((1.005)^60 - 1) / 0.005]

≈ 200 * [ (1.34885 - 1) / 0.005 ]

≈ 200 * (69.77)

≈ 13,954

Total contributions = 200 * 60 = 12,000

Estimated growth from interest ≈ 1,954

If contributions are at the beginning of each period (annuity due)

Multiply by (1 + i):

FV_due = FV * (1 + i)

6) Savings Goal Formula: “How Much Do I Need to Save Each Month?”

If you have a target future value and want to solve for the payment:

Payment required for a target future value

PMT = FV * [ i / ((1 + i)^n - 1) ]

Example: You want FV = 25,000 in 4 years at 5% annual compounded monthly.

i = 0.05/12n = 48

PMT = 25,000 * [ (0.05/12) / ((1 + 0.05/12)^48 - 1) ]

This is a direct, practical formula for planning.

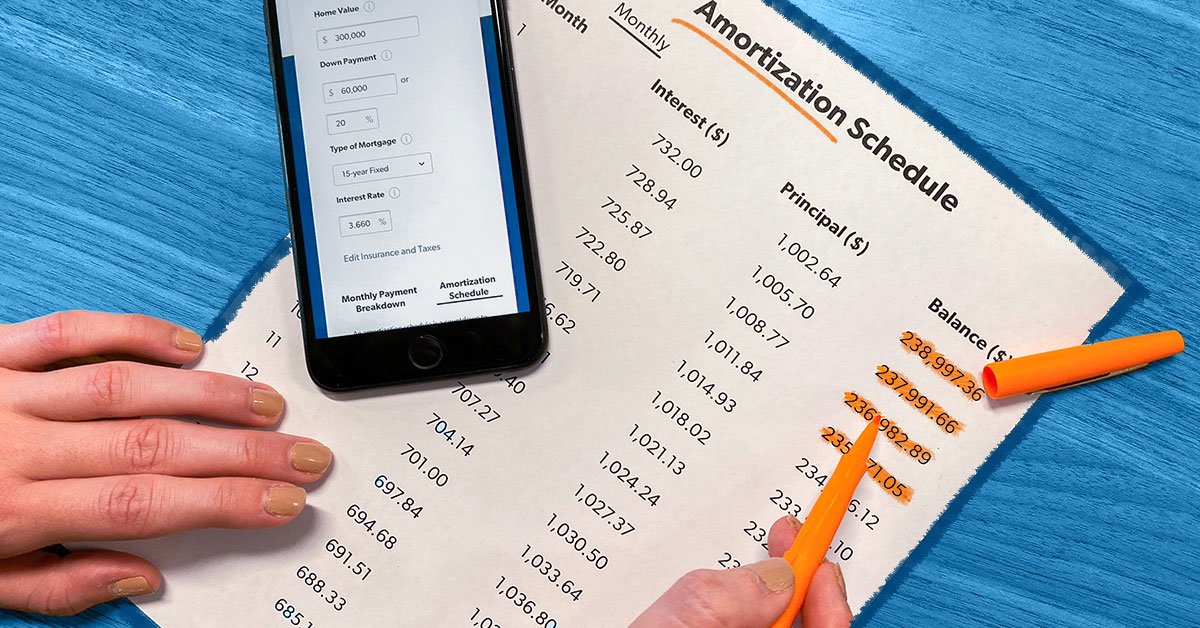

7) Loan Payments: The Amortization Formula

A standard installment loan (fixed payment, fixed rate) uses an annuity structure in reverse.

Monthly payment for a loan

PMT = P * [ i * (1 + i)^n / ((1 + i)^n - 1) ]

Where:

Pis the loan principaliis the periodic (monthly) ratenis total number of payments

Example: Borrow P = 120,000 for 10 years at 7% annual, monthly payments.

i = 0.07/12 ≈ 0.005833333n = 120

PMT = 120,000 * [ 0.00583333 * (1.00583333)^120 / ((1.00583333)^120 - 1) ]

You can compute this with any calculator, but what matters conceptually is:

- The payment is designed so the loan reaches zero exactly at the last period

- Early payments are interest-heavy

- Later payments are principal-heavy

Interest and principal split (per payment)

For a given month:

Interest_t = Balance_(t-1) * i

Principal_t = PMT - Interest_t

Balance_t = Balance_(t-1) - Principal_t

Mini amortization illustration (conceptual)

| Month | Start Balance | Interest | Principal | End Balance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 120,000 | Balance × i | PMT − interest | Lower |

| 2 | Slightly lower | Lower | Slightly higher | Lower |

| … | … | … | … | … |

The core insight: the same payment behaves differently over time.

8) Remaining Loan Balance After k Payments

Sometimes you want to know the balance after a certain number of payments (for refinancing, early payoff, or planning).

Remaining balance formula

Balance_k = P * (1 + i)^k - PMT * [((1 + i)^k - 1) / i]

This is useful for “what if I pay extra?” scenarios because it lets you compare balances under different payment amounts.

9) Total Cost of a Loan (And Why Rate Alone Is Not Enough)

The nominal rate is not the whole story. Fees, compounding, and timing can change the true cost.

Total paid and total interest (simple, but informative)

Total_paid = PMT * n

Total_interest = Total_paid - P

Even if two loans have similar interest rates, differences in fees or terms (length) can dominate the total interest paid.

Example: same principal, different term lengths

| Principal | Rate (annual) | Term | Payment | Total Paid | Total Interest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100,000 | 6% | 10 years | Higher | Lower | Lower |

| 100,000 | 6% | 25 years | Lower | Higher | Much higher |

Longer terms reduce monthly burden but increase total interest significantly.

10) Inflation Adjustment: Real Value and Real Return

A return that looks positive in nominal terms can be disappointing in real purchasing power.

Real return (more accurate version)

Real_return = (1 + nominal_return) / (1 + inflation) - 1

Example: nominal return 8%, inflation 3%

Real_return = 1.08 / 1.03 - 1 ≈ 0.04854 (4.854%)

Converting “today’s money” to future cost (inflation growth)

Future_cost = Cost_today * (1 + inflation)^years

Example: a cost of 10,000 today, inflation 3% for 15 years:

Future_cost = 10,000 * (1.03)^15 ≈ 15,579

Inflation math is not optional for long-range planning.

11) Investment Return Formulas You Actually Use

Simple return (one period)

Return = (Ending_value - Beginning_value) / Beginning_value

Compound annual growth rate (CAGR)

CAGR is a clean way to express growth over multiple years.

CAGR = (Ending / Beginning)^(1/years) - 1

Example: 5,000 grows to 8,000 over 6 years:

CAGR = (8,000/5,000)^(1/6) - 1

= (1.6)^(0.1667) - 1

≈ 0.0813 (8.13%)

CAGR is a smoothing metric; actual year-to-year results can vary widely.

Expected return (basic weighted average)

If you have multiple scenarios:

Expected_return = Σ (probability_i * return_i)

Example:

- 30% chance of +12%

- 50% chance of +6%

- 20% chance of −5%

Expected = 0.3*0.12 + 0.5*0.06 + 0.2*(-0.05)

= 0.036 + 0.03 - 0.01

= 0.056 (5.6%)

This is not a guarantee; it’s a planning average.

12) Risk in One Page: Volatility and Drawdowns

Finance math is not only about growth; it’s also about uncertainty.

Standard deviation (conceptual)

Standard deviation measures how dispersed returns are around the average. Higher dispersion generally means higher volatility.

You do not need to compute it manually to use the concept: the practical lesson is that two investments can have the same average return but very different lived experiences.

Drawdown (what people actually feel)

Drawdown is a peak-to-trough decline:

Drawdown = (Trough - Peak) / Peak

Example: if your value goes from 50,000 down to 40,000:

Drawdown = (40,000 - 50,000) / 50,000 = -0.20 (-20%)

13) Quick Reference Tables

Table A: Compounding Growth of 1,000 Over 10 Years

Assume annual compounding for simplicity.

| Annual Rate | Future Value in 10 Years |

|---|---|

| 2% | 1,000*(1.02)^10 ≈ 1,219 |

| 5% | 1,000*(1.05)^10 ≈ 1,629 |

| 8% | 1,000*(1.08)^10 ≈ 2,159 |

| 10% | 1,000*(1.10)^10 ≈ 2,594 |

Small rate changes are amplified by time.

Table B: Rule of 72 (Fast Doubling Estimate)

Rule of 72 estimates the years to double:

Years_to_double ≈ 72 / (rate_percent)

| Rate | Years to Double (Approx.) |

|---|---|

| 3% | 24 |

| 6% | 12 |

| 8% | 9 |

| 12% | 6 |

It’s an approximation, but good for quick intuition.

14) Three Worked Examples (Start-to-Finish)

Example 1: Compare “save more” vs “earn more” on savings

You want to build a fund in 5 years.

- Option A: save 250 per month at 4% annual compounded monthly

- Option B: save 200 per month at 6% annual compounded monthly

Use:

FV = PMT * [((1 + i)^n - 1) / i]

Option A:

PMT = 250i = 0.04/12n = 60

Option B:

PMT = 200i = 0.06/12n = 60

What you learn conceptually:

- Higher contributions usually dominate over small rate improvements in short horizons

- Over longer horizons, rate differences become more meaningful

This helps you prioritize: increase savings rate first, then optimize return.

Example 2: Two loans with the same principal, different terms

You borrow 80,000 at 7% annual.

- Loan 1: 5 years (60 months)

- Loan 2: 12 years (144 months)

Same principal, same rate, different term:

PMT = P * [ i * (1 + i)^n / ((1 + i)^n - 1) ]

Conceptual outcome:

- The 12-year loan will have a lower payment

- But total interest will be much higher

- The “cheaper monthly payment” is often an expensive trade-off

Example 3: Convert nominal investment returns into real purchasing power

You invest 10,000 for 15 years.

- Nominal return: 7%

- Inflation: 3%

Nominal future value:

FV_nominal = 10,000 * (1.07)^15 ≈ 27,590

Real return:

Real_return = 1.07/1.03 - 1 ≈ 0.03883 (3.883%)

Real future value (in today’s purchasing power):

FV_real = 10,000 * (1.03883)^15 ≈ 17,690

The nominal balance looks impressive, but the real-value view is what matters for long-term goals.

15) Common Mistakes That Create Expensive Confusion

- Mixing annual rates with monthly periods

Always convert:i = r/12andn = years*12for monthly calculations. - Comparing nominal rates instead of effective rates

UseEAR = (1 + r/m)^m - 1to compare properly. - Ignoring inflation

A nominal gain is not the same as improved purchasing power. - Focusing only on monthly payment

Always check total cost:Total_paid = PMT*n. - Assuming averages reflect lived results

CAGR smooths; real returns can be uneven, with drawdowns.

FAQs: Finance Math

1) What is the single most important formula in personal finance?

Compounding:

FV = P * (1 + i)^n

It drives both savings growth and debt costs.

2) Why do loan payments feel like they “barely reduce the balance” at first?

Because interest is calculated on the outstanding balance:

Interest_t = Balance_(t-1) * i

Early on, the balance is highest, so the interest portion is largest.

3) How do I compare a savings rate that compounds monthly to one that compounds annually?

Convert both to effective annual rate:

EAR = (1 + r/m)^m - 1

4) What’s the difference between PV and FV?

FVtells you what money becomes in the future with growth.PVtells you what future money is worth today when discounted:

PV = FV / (1 + i)^n

5) How can I estimate how long it takes money to double?

Rule of 72:

Years_to_double ≈ 72 / rate_percent

6) If I want a specific target amount, how do I find the monthly savings required?

Solve for payment:

PMT = FV * [ i / ((1 + i)^n - 1) ]

7) What’s the cleanest way to express multi-year investment performance?

CAGR:

CAGR = (Ending / Beginning)^(1/years) - 1

8) What does “real return” mean, and why should I care?

Real return is your return after inflation:

Real_return = (1 + nominal_return) / (1 + inflation) - 1

It reflects actual purchasing power growth.

9) Is a lower monthly payment always better?

Not necessarily. Lower payment often means a longer term and higher total interest:

Total_interest = (PMT * n) - P

10) What should I calculate first when comparing two financial options?

Start by aligning the basics:

- Same time units (monthly vs annual)

- Same effective rate

- Same definition of “cost” (total paid, real return, fees included)