“Payment amount” sounds simple: it’s the amount you pay each period (monthly, biweekly, weekly) toward a loan, credit balance, subscription, or installment plan. But in finance, payment amounts can mean very different things depending on the agreement:

- A fixed installment that pays off a loan over time (amortized payment)

- An interest-only payment that doesn’t reduce principal

- A minimum payment on a credit card that may barely reduce the balance

- A balloon payment due at the end

- A partial payment that changes future interest and payoff timing

If you’re building financial calculators or writing finance content, payment amounts matter because they determine affordability, total interest paid, and payoff time. This article explains the main types of payment amounts, the math behind each one, and how to calculate payments correctly using formulas.

What Does “Payment Amount” Mean?

A payment amount is the amount paid at a defined interval to meet an obligation. The key details are:

- Interval (monthly, biweekly, weekly)

- Interest model (amortized, simple interest, interest-only, revolving)

- Term (how long payments last)

- Fees (can change the effective payment)

- Payment timing (end of period vs beginning)

Two loans can have the same principal and interest rate but very different payment amounts if the term differs or if one is interest-only.

The Most Common Types of Payment Amounts

1) Amortized (Installment) Payments

Used for mortgages, auto loans, personal loans, many business loans.

- Payment amount is usually fixed

- Each payment includes interest + principal

- Interest portion is higher at the start, principal portion grows over time

2) Interest-Only Payments

Used in some mortgages, investment loans, short-term financing.

- Payment covers interest only

- Principal doesn’t decrease (unless you pay extra)

3) Minimum Payments (Revolving Credit)

Used for credit cards and lines of credit.

- Payment is typically a small % of balance (or a floor amount)

- Can lead to very long payoff times

4) Balloon Payments

Used in some financing deals.

- Smaller regular payments

- Large final payment due at end

5) Simple-Interest Installments (Daily Accrual)

Used in some “simple interest loans” where interest accrues daily on outstanding balance.

- Payment schedules resemble amortization

- Total interest depends heavily on payment timing

Payment Amounts for Amortized Loans (Most Important Case)

Variables you’ll use

- P = loan principal

- APR_percent = annual interest rate in percent

- APR = annual interest rate in decimal

- payments_per_year = 12 (monthly), 26 (biweekly), 52 (weekly)

- i = periodic interest rate (APR / payments_per_year)

- years = loan term in years

- n = total number of payments (years * payments_per_year)

- PMT = payment amount per period

Step 1: Convert APR to decimal and periodic rate

APR = APR_percent / 100

i = APR / payments_per_year

n = years * payments_per_year

Step 2: Amortized payment formula (fixed payment)

PMT = P * (i * (1 + i)^n) / ((1 + i)^n - 1)

This formula assumes:

- payments are made at the end of each period

- interest is applied each period at rate i

- payment stays constant

If APR is 0 (zero interest), handle it separately:

if APR == 0:

PMT = P / n

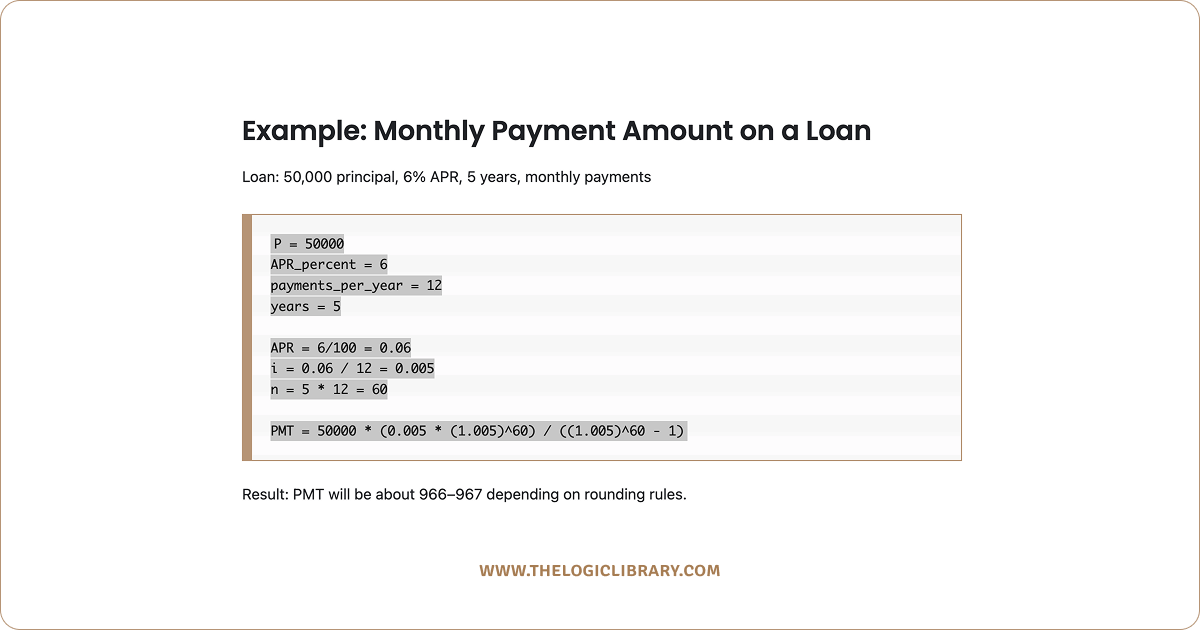

Example: Monthly Payment Amount on a Loan

Loan: 50,000 principal, 6% APR, 5 years, monthly payments

P = 50000

APR_percent = 6

payments_per_year = 12

years = 5

APR = 6/100 = 0.06

i = 0.06 / 12 = 0.005

n = 5 * 12 = 60

PMT = 50000 * (0.005 * (1.005)^60) / ((1.005)^60 - 1)

Result: PMT will be about 966–967 depending on rounding rules.

What this means: your payment amount is roughly 967 per month. Over time, the interest portion drops and the principal portion rises, but the payment amount stays the same.

Breaking a Payment Amount Into Interest and Principal

For any given period:

- Interest is computed on the current balance

- The rest of the payment reduces principal

Let balance_before be the balance right before a payment.

interest_payment = balance_before * i

principal_payment = PMT - interest_payment

balance_after = balance_before - principal_payment

This is how amortization schedules are built.

Remaining Balance After k Payments

If you want the remaining balance without creating a full schedule:

Let k be the number of payments already made (k from 0 to n).

balance_k = P * (1 + i)^k - PMT * (((1 + i)^k - 1) / i)

This is useful for:

- payoff quotes

- refinance math

- comparing extra payment strategies

Total Interest Paid Over the Full Term

For a standard amortized loan:

total_paid = PMT * n

total_interest = total_paid - P

This is a simple but powerful way to compare payment amounts across different terms.

Why Payment Amounts Change

1) Principal (P)

Higher principal means higher payment.

2) APR (interest rate)

Higher APR increases payment, especially at longer terms.

3) Term length (years)

Longer terms reduce payment amount but often increase total interest.

4) Payment frequency

Biweekly vs monthly changes:

- periodic rate

- number of payments

- effective payoff time (especially if biweekly is “half payment every 2 weeks”)

5) Fees and add-ons

If fees are rolled into the loan balance, they raise P and increase PMT.

Monthly vs Biweekly Payment Amounts

There are two common “biweekly” setups:

A) True biweekly amortization (26 payments/year)

payments_per_year = 26

i = APR / 26

n = years * 26

PMT_biweekly = P * (i * (1 + i)^n) / ((1 + i)^n - 1)

B) “Half the monthly payment every 2 weeks”

This results in 26 half-payments, which equals 13 full monthly payments per year. That extra payment effect can shorten the term.

PMT_monthly = ...

biweekly_payment = PMT_monthly / 2

This method can pay the loan off earlier because you effectively pay one extra monthly payment per year.

Interest-Only Payment Amounts

Interest-only payments are simpler.

Let balance be the principal (if no principal is paid down), and i be the periodic rate.

Monthly interest-only payment:

APR = APR_percent / 100

i = APR / 12

PMT_interest_only = P * i

Example: P = 300,000 at 6% APR

P = 300000

APR = 0.06

i = 0.06/12 = 0.005

PMT_interest_only = 300000 * 0.005 = 1500

Important: You still owe the full principal later unless you pay it down.

Balloon Payment Structures

A balloon structure might have:

- smaller periodic payments

- a large final payment due at the end

One common version is: calculate a payment amount as if amortized over a longer period, but the loan ends earlier, leaving a remaining balance as the balloon.

Example concept:

- amortize over 30 years

- loan term is 5 years

- balloon = remaining balance after 5 years

PMT = payment_based_on_amortization_term

balloon = balance_after_k_payments

Using the remaining balance formula:

balloon = P * (1 + i)^k - PMT * (((1 + i)^k - 1) / i)

Where k is the number of payments made before the balloon is due.

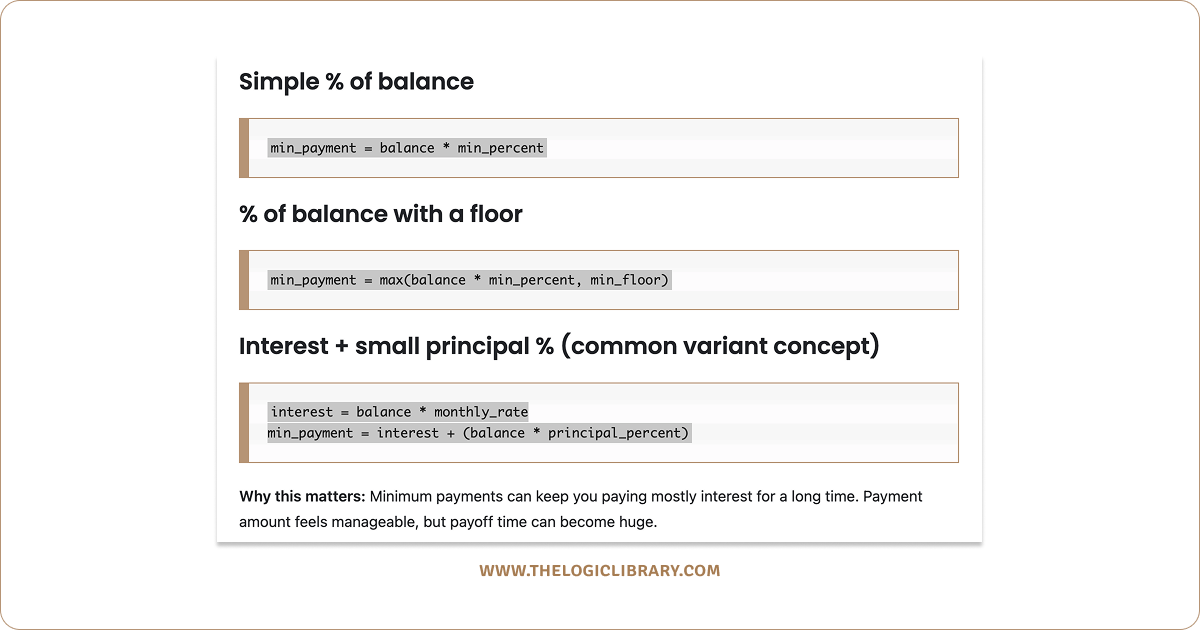

Credit Card Minimum Payment Amounts

Minimum payment rules vary, but often look like one of these:

Simple % of balance

min_payment = balance * min_percent

% of balance with a floor

min_payment = max(balance * min_percent, min_floor)

Interest + small principal % (common variant concept)

interest = balance * monthly_rate

min_payment = interest + (balance * principal_percent)

Why this matters: Minimum payments can keep you paying mostly interest for a long time. Payment amount feels manageable, but payoff time can become huge.

Payment Amounts With Extra Payments

Extra payments reduce principal faster and can reduce total interest. There are two common patterns:

A) Pay extra every period

effective_payment = PMT + extra

Then principal reduction increases, balance falls faster, and the loan ends earlier.

B) One-time lump sum extra payment

At some point k:

balance_after_extra = balance_k - lump_sum

Then continue amortization from the lower balance.

Recasting vs Refinancing (When Payment Amount Changes)

- Recast: you pay a lump sum, lender recalculates payment amount based on new balance and remaining term (not always available).

- Refinance: you replace the loan with a new one (new rate/term/costs), producing a new payment amount.

For a recast-style payment recalculation:

P_new = updated_balance

PMT_new = P_new * (i * (1 + i)^(n_remaining)) / ((1 + i)^(n_remaining) - 1)

How to Solve for Term When You Know Payment Amount

Sometimes you know:

- P

- APR

- PMT

and you want to find n (number of payments).

You can solve using logs.

n = log(PMT / (PMT - P*i)) / log(1 + i)

Where:

- i = periodic rate

- PMT must be greater than P*i, otherwise payment doesn’t cover interest

This is useful for:

- “If I can pay X per month, how long will it take?”

How to Solve for Principal When You Know Payment Amount

If you know PMT, i, and n, you can solve for P:

P = PMT * ((1 + i)^n - 1) / (i * (1 + i)^n)

This is the backbone of affordability calculators:

- “Given my monthly budget, how much can I borrow?”

Rounding Rules and Why Your Numbers Don’t Match

Even if your formula is correct, real lenders may differ due to:

- periodic rounding of interest (daily vs monthly rounding)

- interest computed using 360-day vs 365-day conventions

- payment applied rules (interest-first vs different allocations)

- fees added to balance

- payment timing (beginning-of-period vs end-of-period)

For calculators, choose a consistent method and disclose it clearly.

Payment Amounts Checklist

Use this to prevent common errors:

- Confirm payment frequency: monthly, biweekly, weekly

- Convert APR correctly:

APR = APR_percent / 100

i = APR / payments_per_year

- Confirm term in number of payments:

n = years * payments_per_year

- Use correct formula for the product type:

- amortized installment

- interest-only

- revolving minimum payment

- balloon structure

FAQs About Payment Amounts

What is a payment amount?

It’s the amount paid per period toward a debt or obligation. In loans, it usually includes both interest and principal.

Why is my payment amount mostly interest at the beginning?

Because interest is calculated on the outstanding balance. Early on, the balance is highest, so interest is highest. With a fixed payment, that leaves less room for principal reduction initially.

Does a longer term always lower the payment amount?

Usually yes (for amortized loans), but it often increases total interest paid.

What happens if my payment doesn’t cover interest?

Your balance may not decrease and can even grow (negative amortization) depending on the contract. A safe condition for amortized payoff is:

PMT > P * i

How do I reduce my payment amount?

Common options are:

- extend term (if lender allows)

- lower interest rate (refinance)

- reduce principal (bigger down payment or lump-sum payment + recast if available)

How do extra payments affect my payment amount?

Extra payments usually reduce payoff time and total interest. The regular payment amount may not change unless the loan is recast.

Summary

Payment amounts are not one-size-fits-all. The meaning depends on whether you’re dealing with an amortized loan, interest-only structure, revolving credit minimums, or a balloon agreement. For most installment loans, the fixed payment amount is calculated with:

APR = APR_percent / 100

i = APR / payments_per_year

n = years * payments_per_year

PMT = P * (i * (1 + i)^n) / ((1 + i)^n - 1)

Once you understand this, you can:

- estimate monthly payments

- compare loan terms

- calculate total interest

- model extra payments

- compute remaining balances