Simple interest is one of the most practical financial concepts you can learn because it shows up in real borrowing and saving situations and it’s easy to verify with basic math. When interest is calculated using a simple interest method, the interest is based only on the original amount of money — the principal. That means the interest does not “stack” on top of previous interest the way it does with compounding.

If you’re trying to estimate how much a loan will cost, how much you can earn on a basic investment, or whether a quoted rate makes sense, simple interest gives you a reliable baseline. It’s also the foundation for understanding more complex ideas like compound growth, amortized loans, APR comparisons, and daily accrual.

This guide explains simple interest in plain language, gives accurate formulas, and includes many examples (years, months, and days). You’ll also learn how to solve for missing values (rate, time, principal), how to avoid common mistakes, and how to interpret “simple interest” in real contracts.

What Is Simple Interest?

Simple interest is interest calculated only on the original principal for the entire time period.

- Principal stays the same in the interest calculation.

- Interest grows in a straight line with time.

- Doubling time doubles interest (if rate and principal stay the same).

- Doubling the rate doubles interest (if principal and time stay the same).

- Doubling the principal doubles interest (if rate and time stay the same).

That linear behavior is why simple interest is quick to estimate.

Key Terms You Must Know

Before you calculate anything, you need to know what each symbol represents:

- P = principal (starting amount)

- rate_percent = interest rate expressed as a percent (like 8 for 8%)

- r = interest rate expressed as a decimal (like 0.08)

- t = time in years (unless stated otherwise)

- I = total interest over the full time period

- A = total amount after interest (principal + interest)

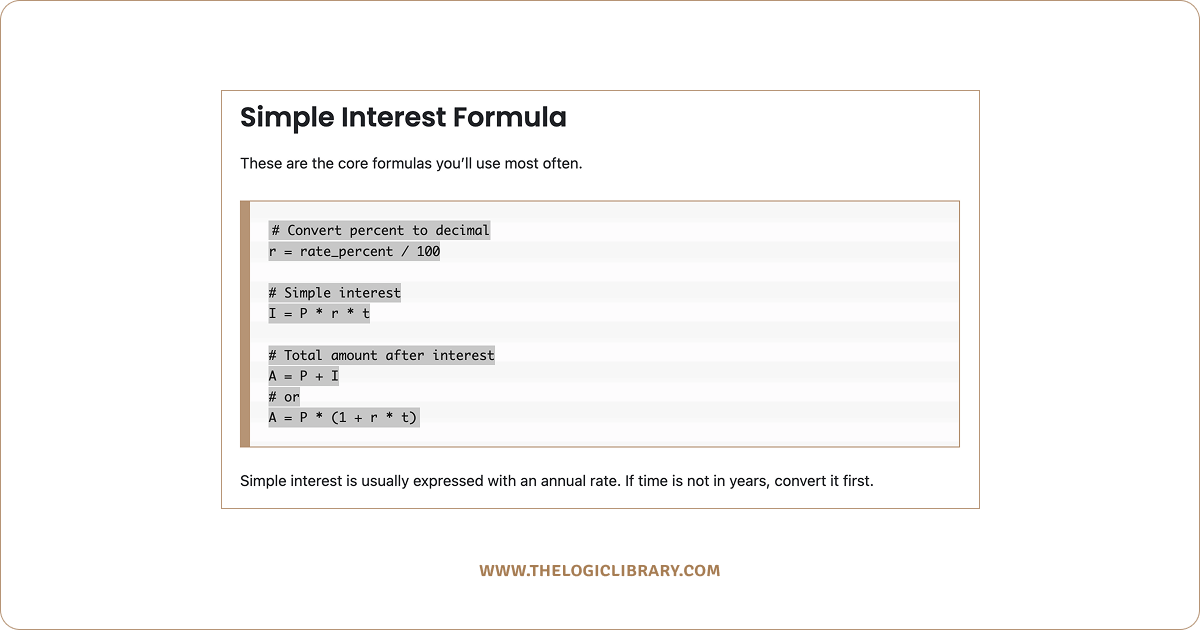

Simple Interest Formula

These are the core formulas you’ll use most often.

# Convert percent to decimal

r = rate_percent / 100

# Simple interest

I = P * r * t

# Total amount after interest

A = P + I

# or

A = P * (1 + r * t)

Simple interest is usually expressed with an annual rate. If time is not in years, convert it first.

Time Conversion (Months and Days)

Incorrect time units are the #1 reason people get wrong answers. If the rate is annual, time must be expressed in years.

Months to years

t = months / 12

Examples:

- 3 months -> t = 3/12 = 0.25

- 6 months -> t = 6/12 = 0.5

- 9 months -> t = 9/12 = 0.75

- 18 months -> t = 18/12 = 1.5

Days to years (365-day method)

t = days / 365

Days to years (360-day method)

Some contracts use 360 days (common in certain commercial conventions). It produces slightly higher interest for the same number of days.

t = days / 360

If you’re doing personal finance estimates and no convention is specified, 365 is usually the safer default.

How Simple Interest Works (The Intuition)

Simple interest behaves like “rent” you pay for using money.

- If you borrow money, the interest is the cost of using it.

- If you lend or invest money, the interest is the income you earn by letting someone else use it.

Because it’s linear, simple interest is predictable. For example, with a 10% annual rate, each year adds 10% of the original principal as interest, not 10% of the growing total.

Step-by-Step Simple Interest Calculation

Use this process every time:

- Write down principal P

- Write down annual rate in percent (rate_percent)

- Convert rate_percent to r (decimal)

- Convert time to years (if needed)

- Calculate interest I

- Add principal to get total A

Template:

P = (principal)

rate_percent = (annual rate in %)

t = (time in years)

r = rate_percent / 100

I = P * r * t

A = P + I

Example 1: Basic Loan (Years)

You borrow 2,000 at 8% per year for 3 years.

P = 2000

rate_percent = 8

t = 3

r = 8/100 = 0.08

I = 2000 * 0.08 * 3 = 480

A = 2000 + 480 = 2480

Result:

- Interest = 480

- Total to repay = 2,480

Example 2: Savings (Months)

You deposit 5,000 at 4% per year for 18 months.

P = 5000

rate_percent = 4

months = 18

t = months / 12 = 18/12 = 1.5

r = 4/100 = 0.04

I = 5000 * 0.04 * 1.5 = 300

A = 5000 + 300 = 5300

Result:

- Interest earned = 300

- Ending amount = 5,300

Example 3: Short-Term Borrowing (6 Months)

A balance of 1,200 charges 15% per year for 6 months.

P = 1200

rate_percent = 15

months = 6

t = 6/12 = 0.5

r = 15/100 = 0.15

I = 1200 * 0.15 * 0.5 = 90

A = 1200 + 90 = 1290

Result:

- Interest = 90

- Total = 1,290

Example 4: Days-Based Simple Interest (365-Day)

You borrow 2,500 at 7% for 50 days.

P = 2500

rate_percent = 7

days = 50

t = days / 365 = 50/365 = 0.1369863

r = 7/100 = 0.07

I = 2500 * 0.07 * 0.1369863 = 23.9726

A = 2500 + 23.9726 = 2523.9726

Rounded to currency:

- Interest ≈ 23.97

- Total ≈ 2,523.97

Example 5: Days-Based Simple Interest (360-Day)

Same scenario, but 360-day convention.

P = 2500

r = 0.07

days = 50

t = 50/360 = 0.1388889

I = 2500 * 0.07 * 0.1388889 = 24.3056

A = 2524.3056

Compared to 365-day, interest is slightly higher.

Solving for Any Unknown (Reverse Formulas)

Sometimes you don’t need interest — you need the rate, time, or principal.

Start from:

I = P * r * t

Solve for r (rate as decimal)

r = I / (P * t)

Solve for rate_percent (rate as percent)

rate_percent = (I / (P * t)) * 100

Solve for t (time in years)

t = I / (P * r)

Solve for P (principal)

P = I / (r * t)

Example 6: Find the Rate From Interest Earned

You invested 3,000 and earned 270 in interest over 2 years.

P = 3000

I = 270

t = 2

r = 270 / (3000 * 2) = 270/6000 = 0.045

rate_percent = 0.045 * 100 = 4.5

Result:

- Rate = 4.5% per year

Example 7: Find Time Needed

A 10,000 principal at 6% produces 1,200 interest. How long?

P = 10000

rate_percent = 6

I = 1200

r = 6/100 = 0.06

t = I / (P * r) = 1200 / (10000 * 0.06) = 1200/600 = 2

Result:

- Time = 2 years

Example 8: Find Principal Needed

You want to earn 600 interest at 8% over 2.5 years.

I = 600

rate_percent = 8

t = 2.5

r = 0.08

P = I / (r * t) = 600 / (0.08 * 2.5) = 600/0.2 = 3000

Result:

- Principal needed = 3,000

Simple Interest vs Compound Interest (Why Totals Differ)

A lot of people expect interest to grow faster over time. That faster growth comes from compounding, not simple interest.

Simple interest total

A_simple = P * (1 + r * t)

Compound interest total (annual compounding)

A_compound = P * (1 + r)^t

Comparison with P = 1000, rate_percent = 10, t = 3:

P = 1000

r = 0.10

t = 3

A_simple = 1000 * (1 + 0.10 * 3) = 1300

A_compound = 1000 * (1.10)^3 = 1331

Result:

- Simple total = 1,300

- Compound total = 1,331

The difference is the “interest on interest” effect.

Where Simple Interest Is Used (Common Real Scenarios)

Simple interest appears in many places, including:

- short-term loans and notes

- basic lending agreements between individuals

- quick interest estimates for planning

- certain fixed-income instruments that use straightforward interest conventions

- interest problems in education and exams

However, real contracts can be tricky because they may use daily accrual, fees, or repayment schedules that change what you actually pay.

Daily Accrual and the “Simple Interest Loan” Phrase

Sometimes you’ll see “simple interest loan” used in lending to mean interest accrues daily based on the outstanding principal balance. That still isn’t compounding in the investment sense, but it can affect totals if payments are late or early.

If you pay early, you may reduce the interest compared to paying later, because interest accrues based on time. If you pay late, you may pay more interest because more days elapsed.

That’s why time accuracy matters.

Partial Payments: A Practical Simple Interest Approach

In real life, borrowers sometimes make partial payments before the end date. A common simple-interest method is:

- Calculate interest up to the payment date

- Apply payment first to interest (if contract says so), then reduce principal

- Continue accruing interest on the new principal for the remaining time

Basic model (two periods):

# Period 1

I1 = P * r * t1

P_new = P - payment_applied_to_principal

# Period 2

I2 = P_new * r * t2

I_total = I1 + I2

A_total = P_new + I2 # if principal still outstanding at end

This is a simplified framework; real contracts can allocate payments differently, but this shows how timing changes interest under simple accrual.

How to Spot and Avoid Common Simple Interest Mistakes

Mistake 1: Using percent as decimal

Wrong:

I = 2000 * 8 * 3

Correct:

r = 8/100

I = 2000 * r * 3

Mistake 2: Using months as years

Wrong:

t = 18

Correct:

t = 18/12 = 1.5

Mistake 3: Mixing day conventions

If a contract uses 360 days and you calculate using 365 days, your result won’t match theirs. Always check the method if precision matters.

Mistake 4: Forgetting currency rounding

In many cases, you’ll compute many decimals. In practice, interest is rounded to cents (or the smallest currency unit), often at specific points (daily, monthly, or at payoff).

Quick Estimation Tricks (Fast Mental Math)

Simple interest is linear, so estimation is easy.

- 10% of P = P / 10

- 5% of P = P / 20

- 2% of P = P / 50

- 1% of P = P / 100

Then multiply by time (in years).

Example: P = 8,000 at 5% for 3 years

1-year interest = 8000 * 0.05 = 400

3-year interest = 400 * 3 = 1200

Total = 8000 + 1200 = 9200

Simple Interest in Business: Markups, Financing, and Notes

Businesses often use simple interest calculations for short-term financing because they’re easy to quote and easy to reconcile.

For example, a business might issue a promissory note:

- Principal: 50,000

- Annual rate: 9%

- Term: 120 days

Using 365-day:

P = 50000

r = 0.09

t = 120/365

I = 50000 * 0.09 * (120/365)

I = 1479.4521

A = 51479.4521

Even if a business later refinances into a different structure, this method is frequently used for short terms.

Simple Interest vs “Flat Rate” (Important Clarification)

A flat rate is often described as “interest calculated on the original amount,” which sounds like simple interest — but flat-rate quoting can hide the effective cost when payments are made over time.

Why? Because if you’re making monthly payments, your balance is declining. If someone charges interest as if the full principal stayed outstanding the whole time, the effective annual cost can be much higher than it appears.

A safe rule:

- Always compare total repayment and timing, not just the headline rate.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the simple interest formula?

r = rate_percent / 100

I = P * r * t

A = P + I

How do you calculate simple interest for months?

Convert months to years:

t = months / 12

I = P * r * t

How do you calculate simple interest for days?

Use a day-count method:

t = days / 365

# or if required

t = days / 360

I = P * r * t

Does simple interest mean the payment is the same every month?

Not necessarily. Simple interest describes how interest is calculated. Payment structure can be monthly, quarterly, or at the end depending on the agreement.

Can simple interest be used for savings?

Yes. Some basic savings arrangements can be modeled with simple interest, especially for short terms or fixed returns.

Is simple interest better than compound interest?

For borrowers, simple interest often costs less than compounding (all else equal). For savers/investors, compounding usually earns more over long periods.

Why doesn’t my lender’s number match my calculation?

Common reasons include:

- 360-day vs 365-day method

- rounding rules (daily/monthly)

- fees added to principal or charged separately

- interest calculated on outstanding balance rather than original principal

- payment timing differences

Summary

Simple interest is the most straightforward interest model because it’s calculated only on the original principal. The essential formulas are:

r = rate_percent / 100

I = P * r * t

A = P + I

# or

A = P * (1 + r * t)

Once you handle time conversion correctly (months/days into years), you can calculate interest quickly, verify quotes, and understand what a rate really means over a given period.